A lot of schools have that in their motto: mental, physical and spiritual. But when you get into the school, you just fight and do forms. When do we get to that part I see at the Shaolin Temple in movies? I’m thinking as I get to the next belt, eventually we’re going to get to that part where the old master is sitting there and he’s teaching you the philosophy. And it never comes. I think kung fu schools – the good ones – are uniquely positioned to be there for that. I know my teacher made us do fighting. He made us do forms. He made us do weapons. We had to do all of it. But he also always made us understand the value of the strength of the internal arts – tai chi.

Denis Brown, Kung Fu Tai Chi, Sept/October 2010.

Introduction

There is an interesting idea floating on the wind. I have now come across it in four or five places since the start of the year. As I read, observe the media, and talk with my friends and colleagues I have heard a number of people state, rather emphatically, that we are on the cusp of a resurgence of interest in the traditional Chinese martial arts. Some individuals are even more specific. It is the “internal arts,” Xingyi, Bagua and especially Taiji Quan that are set to be the next big thing in the American martial arts establishment.

Gene Ching, the editor of Kung Fu Tai Chi Magazine (and a seasoned observer of the martial arts) has spoken about this in a few places. This coming resurgence was the topic of his editorial in the March/April edition of his magazine, and he has also discussed it in greater detail in a recent interview. Nor is this an entirely new prediction. It has been in the air for a few years now.

It goes without saying that I would welcome any such development. The traditional Chinese martial arts enjoyed a huge surge of popularity in the USA (and across most of the world) in the 1970s. Things quieted down in 1980s. Yet by the 1990s they were once again growing at a steady and sustainable rate. However, things began to lag in the early 2000s. This was around the time that Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) really took off.

Since then a number of traditional fighting styles have struggled. Karate and Judo schools have closed, Tae Kwon Do has faced serious challenges and Chinese martial arts styles have declined. Some arts have done better than others. Wing Chun has benefited from the recent spate of Ip Man films, and Taiji has been a clear favorite among many market segments. Yet overall traditional Kung Fu has been though a rough decade and a half.

This is actually a somewhat ironic state of affairs. There is much more reliable information about these arts available to consumers now than there was in the 1970s and 1980s. In general the quality of instruction has also vastly improved. Legions of pioneers have worked out financial and businesses strategies for running schools and clubs. And consumers are just as interested in the traditional arts as ever. Simply look at the sorts of movies and television programs they watch. Notice how often the martial arts are used in television advertising campaigns. On paper the last decade should have been great, but it wasn’t.

I think that one of the less productive responses to this was to blame “kids these days.” The conventional logic seems to go something like this. Kids today are lazy. Lazy and stupid. Lazy, stupid and addicted to their cell phones. They are nothing like we were. They are not the “sort of people” we want in “our arts” anyway.

A slightly more sophisticated version of the same basic argument notes that these kids are also very much into MMA. And the more time you spend in MMA gyms, the less “lazy” these people seem. In fact, it is pretty clear that the MMA movement is producing some incredible athletes and fighters. Yet it also lacks the roots in “traditional Asian culture” that many fans of the eastern martial arts enjoy and find great value in. So we hear instead about how the octagon caters to the “I want it now” generation. Clearly this is a mode of producing and reproducing masculinity, but it lacks a critical “depth of character.” Or so the argument goes.

I suspect that insulting an entire generation of young people for having different values than their parents is not really going to fix anything for the traditional martial arts. As I have argued in a number of other posts, the deep historical continuity and “traditional values” of the Asian fighting arts are mostly a myth. It is not that these arts don’t have and promote values. They certainly do. But the arts themselves undergo a process of radical reform and evolution in each new generation.

With a few exceptions, the cultural values in the average Karate class today have nothing to do with 19th century Okinawan peasants. Instead (if they reflect anything authentic) it is a 1960s era re-imagining of 1930s Japanese cultural values. The exact same thing can be seen in the traditional Chinese arts. Most of these arts date from, or were radically transformed, during the Republic of China period. In fact, prior to the 1920s there were very few public martial arts schools of any kind in China. These arts were again reinterpreted through the lens of 1960s and 1970s popular culture before being transmitted to America.

Our “traditions” are really never quite as ancient as they seem. When you deal with the martial arts it is critical to realize that you are in fact dealing with a product of modernity. As such change is not only possible, it is likely.

In general this is a good thing. It means that the traditional fighting arts can find new and relevant things to say even as our culture and economy shifts. This adjustment can be seen on a lot of levels. It occurs not only within individual arts, but also between the dominate paradigms seen within the martial arts community.

The initial popularity of Judo and Karate in the USA appear to have been a direct response to WWII. Korean and Vietnam led to the growth of Tae Kwon Do. Paul Bowman and others have argued that the American defeat in Vietnam following a decade of social unrest was critical in shaping the Kung Fu craze of the 1970s.

Likewise it does not seem totally inconceivable to me that the more muscular national mood following 9/11, including a turn away from the “Orientalized other,” had something to do with the UFC’s commercial success and the rise of MMA (an idea that had been lingering in the background of western fighting culture since Barton-Wright opened the first Jujitsu salon in London at the start of the 20th century.)

The martial arts reflect and exist in dialogue with larger social trends. As society changes, or they move globally, the nature of those conversations necessarily shifts. Nunchucks in the hands of an Okinawan security guard in the 19th century simply do not mean the same thing as nunchucks in the hands of Bruce Lee on the set of Enter the Dragon. If change is inevitable, then perhaps it makes sense to ask what is next? Will the “internal arts” be the next big thing? And if so why?

Taiji being demonstrated at the famous Wudang Temple, spiritual home of the Taoist arts.

Looking at the Evidence

As the inestimable Yogi Berra once noted, predictions are difficult, especially if they are about the future. Being a political economist by training I am all too aware of this simple truth. Economists in academic settings love to predict things, and it never seems to bother them that they are almost always wrong. Political scientists, on the other hand, are much more reticent to engage in “forecasting” for the simple reason that it is almost mathematically impossible to get this sort of stuff right. Social reality is just too complex. There are too many variables and they can interact in complex and unpredictable ways. In fact, as a field we have a hard enough time just predicting the past (e.g., testing our theories on historical data).

Rather than dragging out a crystal ball and speculating about what the world might look in five years, it might be more sensible to take a detailed look at what we know is going on right now. If a trend has been brewing for the last few years, and is currently picking up steam, we should be able to see it in consumer behavior. Gene Ching is uniquely positioned to deal with social elites and writers in the Chinese martial arts community, so he probably has a pretty good sense of what these individuals are saying. I always find his thoughts on questions like this well worth considering.

Still, no one can lead a movement unless there are a substantial number of people who are willing to follow. What we really need is a way to poll large numbers of potential martial arts students. Ideally we need to be able to look over their shoulder, see what sorts of topics they have been researching and reading about, and find out if they are making any moves toward finding a local Taiji class.

In the past gathering this sort of data would have involved serious survey research which is almost always prohibitively expensive. However, the internet has made each of these tasks much easier. Search engines have virtually replaced hard-bound phone books and business directories at the place that consumers turn to when looking for goods or services.

Many of the largest search providers, including Google, keep records of these searches. Using a simple tool like “Google Trends” it becomes possible to get some very quick and dirty data about what sorts of things consumers are looking for and how their interest in these products has been evolving over the last few years.

I have previously used Google Trends when writing about the declining popularity of the traditional martial arts and found the data to be generally reliable. Nevertheless, there are some caveats to note. The way observations have been aggregated and calculated has changed over time. Further, the more popular a topic is the more reliable and stable the results are. Unfortunately a lot of Chinese martial arts are esoteric by their very nature, meaning that so few people search for them that they either return no search result at all, or the results are not stable.

This is easiest to see when you search for the same topic multiple times using slight different terms (“MMA Class vs. MMA Gym” or “Tai Chi vs. Taiji Quan”) and get very different trend lines. As such care must be taken when specifying your search query. I am not sure that I would be comfortable using these numbers in a published article without doing further checks. Still, with some caution they should suffice for a blog post. On the internet as in life, you get what you pay for.

So with that out of the way, lets look at some data. There might actually be some support for the rumors that MMA is leveling off in popularity. To check this I searched for references to “MMA” on Google Trends over the last several years and restricted the search area to the American media market. Again, to get intelligible results it is often necessary to specify “where” one is searching. I think that what is going on in the USA right now is broadly similar to the situation in much of the western world, but your mileage may vary.

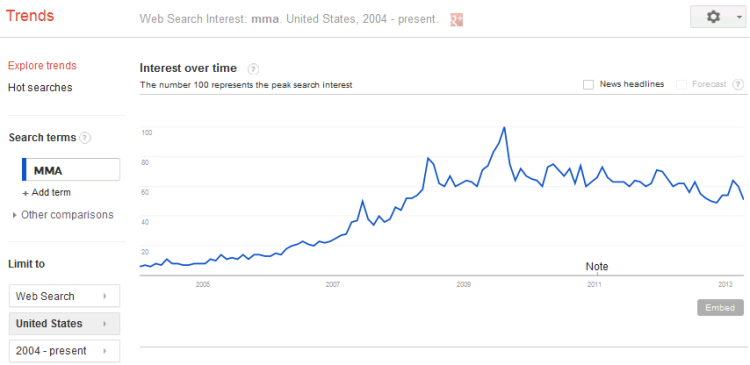

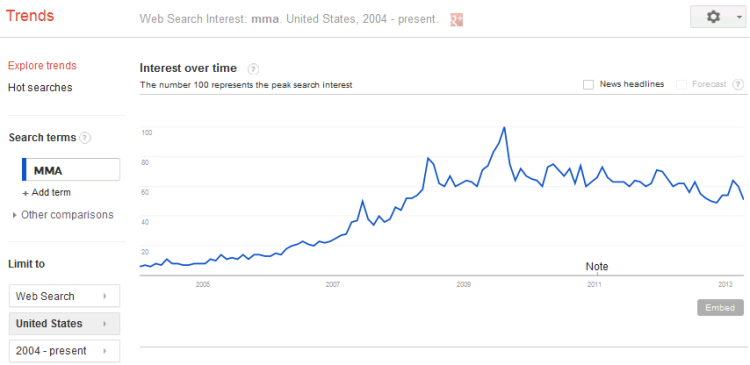

Google Trends Data. Searches for “MMA” over the last ten years.

As we can see from this trend line, searches for Mixed Martial Arts peaked sometime between 2009-2010, and appears to have actually declined very slightly in the last year. Interestingly this same basic trend is seen if we search for “MMA Gym” (a better indicator for those actually planning on training in the sport). That should give us some confidence in the reliability of this data. Given how many people are actually searching for this in absolute terms, Google can generate some trustworthy metrics.

A decline in interest in MMA might indeed open a social space for a new trend. However, interest in the mixed martial arts is still very strong in absolute terms. I wonder if perhaps they actually reached a point of market saturation in the 2009-2010 period? I suspect that we will be seeing large number of MMA gyms for the foreseeable future.

What about the internal arts? That picture is substantially more complicated. To begin with a simple search for something like “Kung Fu” suffers from a high “noise to signal” ratio. Most of these searches are actually directed to popular culture phenomena like “Kung Fu Tea” (the sort you drink) or “Kung Fu Panda.” Turning to the “internal arts” reveals a slightly different set of problems. Xingyi and Bagua Quan are esoteric enough that Google Trends cannot even generate a reliable graph for them. In absolute terms there are just too few people searching for these styles.

Taiji is a different matter. Millions of individuals outside of China have been introduced to this art, and there are probably tens of thousands of serious practitioners in the US alone.

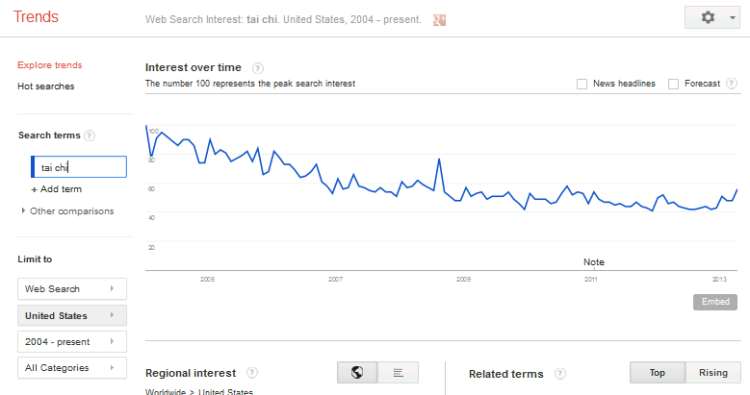

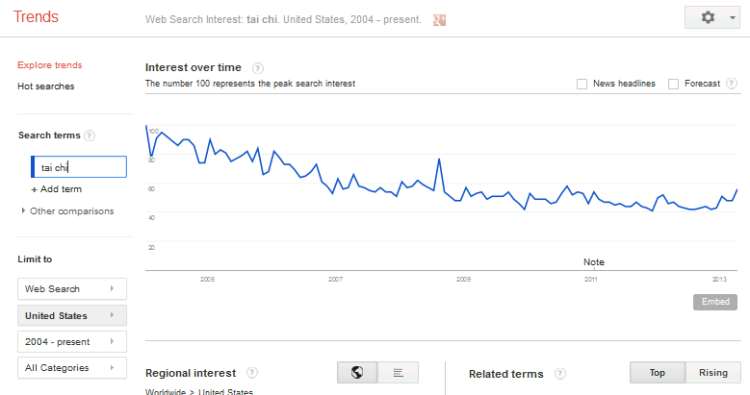

Google Trends Data. Searches “Tai Chi” over the last ten years.

Again, this graph shows an interesting trend over the last decade. Search request (and hence popular interest) for Taiji appear to have peaked in the early 2000s, and declined steadily until sometime in the 2009-2010 time period. They stayed steady at this level for a few years, and now appear to be experiencing a small upsurge in popularity. Interested readers can zoom in on the last 12 month and see this in greater detail if they visit Google Trends.

However, stability is a problem. The same basic pattern of decline, leveling and a possible upswing can be seen if one searches for “Tai Chi Classes.” However, if you switch to the Pinyin spelling (Taiji Quan) Google lacks the requisite number of raw queries to generate a trend line.

Searches for “Tai Chi Form” show a similar pattern of decline in the middle of the 2000s, but leveling off by 2007. Unfortunately they show no upsurge of interest in the last few years. Likewise searches for “Tai Chi Sword” have actually continued to decline in a uniform manner. “Tai Chi Jian” did not return any trend line.

Yang, Chen, Wu and Sun styles all reflect similar trend patterns to the aggregate “Tai Chi” query. Of these the Yang style shows the clearest upsurge in interest while the others are basically flat. Different variations of searches for “push hands” exercises also remained fairly flat from the late 2000s onward.

The recent trend data appears to be mixed. There may be some support for concluding that MMA has peaked (or probably more accurately, reached a point of market saturation). Yet it is not clear that the internal arts must logically follow. While there are some signs of resurgence in the Taiji community, much of the picture is mixed. Many trends are flat, and those that are rising in the last 12 months have yet to come anywhere close to making up the ground that they lost between 2001 and 2009. It could be the case that a trend is starting, but we have yet to see a really clear change in consumer behavior (at least in the aggregate national date.)

A trip to any public park in China would seem to indicate that the average age of traditional martial artists is increasing. At the same time these individuals may have a greater need for strong social networks and have more resources to devote to finding them.

Three Approaches to Understanding the Popularity of the Martial Arts

It is probably not surprising that we do not have a clear trend in the data. After all, such questions are not really fun to discuss after the answer is clear to everyone. Still, this raises the more important question of why martial arts styles or movements become popular in the first place. Why have the traditional arts been more popular at some times and in some places than others?

Different writers and scholars have offered a number of answers. These theories can be grouped into three broad approaches. Obviously there are other schools of thought out there, but these are the three that I hear the most often and they seem like a good place to start the discussion. Also I should note that while I am about to treat these as three different schools of thought, that is largely a result of the types of scholars that pursue them and the questions that they personally find interesting. On a deeper theoretical level each of these approaches blends with the others.

Those caveats aside, it seems to me that there are three basic approaches that we might want to consider when thinking about the future popularity of the internal martial arts. These are the materialist/historical school, the question of identity formation and lastly the sociological approach.

Materialist/Historical

I suspect that the historical school is the one that most casual readers will be familiar with. Military historians like Henning and Lorge fall into this camp, as do (to a lesser degree) other historians such as Shahar or Robinson. The basic assumption that all of these authors make is that martial culture exists in a knowable realm defined primarily by non-negotiable facts. These facts might be economic in nature. Some areas of China are rich in natural resources, and others are prone to flooding. This will certainly have an important impact on the development of local society and the martial arts.

Occasionally these facts are political or social. For instance, a variety of historians have noted that the popularity of the martial arts increased in times of social decay. The late Ming and the Qing both saw important advances in the Chinese martial arts as community and personal defense became serious concerns for many members of Chinese society.

Occasionally these “facts” are a little harder to directly observe, but they still tend to be the result of tangible causes. For instance, Nancy Chen, attempting to situate the start of China’s Qigong craze in the 1980s, noted that what seemed to be a spiritual awakening was really happening on the heels of two much more political events. One was the end of the Cultural Revolution, which left many individuals with deep emotional scars they were not able to express publicly. The other was recent attempts to reform the Chinese medical system by switching to a “fee for service” model which effectively denied most of the country timely access to modern scientific medicine. As a result of both of these trends interest in Qigong, which could induce feelings of well-being and was fairly inexpensive compared to either herbal or western medicine, exploded.

This last step in her chain of reasoning reveals something critical about the materialist/historical approach. It often (though by no means always) presupposes that the subjects of the study will react rationally to these historically given changes in their environment. Perhaps this assumption of “rationality” is the easiest to defend in the realm of military history, where the environment itself is deadly and will impose severe sanctions on anyone who miscalculates its essential nature. In such a realm the ever present possibility of force may be seen as structuring action.

But even in the more nuanced milieu that Chen describes (much of her research focuses on the cross-cultural study of mental illness) she still assumes that people behave essentially rationally. When the price of a good goes up they simply switch to a lower cost alternative. Identity, norms or culture have nothing to do with it. The rise of Qigong was essentially a market driven conclusion.

Such an approach offers some immediate and interesting predictions about the future of the internal arts in America (and the western world more generally). A large number of baby boomers have had some experience with the traditional martial arts, and these individuals are not getting any younger. For better or worse Taiji has developed a reputation as an ideal art for senior citizens. It can help with the maintenance of chronic health conditions, it is a great low impact form of exercise and qigong training offers benefits in dealing with the aches and pains of aging. Further, the price of healthcare in this country is headed in the wrong direction. It is not inconceivable that the same market based drive for alternative medicines that Chen noted in China might not become a reality here.

The Question of Identity

Still, such an approach is not without its pitfalls. Rationality implies a system of universal and unchanging signs and symbols, yet these things are almost always socially constructed. Even basic concepts like “violence,” “employment” or “mental illness” are all socially negotiated and framed. They become real in our life through a mutual understanding of what these things mean. For instance, using Qigong as a treatment for chronic pain makes more sense in some societies than others because of their understanding of what the ultimate roots of that pain are and the meaning of suffering in life.

In this sort of a constructivist setting “identity” becomes a central issue because your position in society and understanding of self frames practically everything that one comes in contact with. Nor are identities simply given; they are negotiated. Individuals can attempt to reshape their identity or conception of self in an attempt to improve either their social standing or basic emotional state. Yet this reshaping of identity never happens in a vacuum. Instead it is bounded by the signs and symbols that are available in the local environment.

Very often discussions coming out of this mode start with the observation that Chinese martial artists are socially “marginal” people. Daniel Miles Amos was one of the first students of Chinese martial culture to explore this avenue in his 1983 doctoral dissertation titled “Marginality and the Heroes Art: Martial Artists in Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton).” Similar themes have been picked up by Adam D. Frank, Avron Boretz and Paul Bowman.

For such theorists the martial arts become a vehicle for escaping or reframing this marginality. Historians of the materialist school are quick to point out that the traditional Chinese martial arts were often seen as a potential avenue of social advancement for underprivileged youth from the country. A martial education might lead to a military career, or a higher paying job as a guard in the city.

Yet martial training deals with the issue of “marginality” in more subtle ways as well. Martial arts schools become locations where it is possible for individuals to build status and earn a type of prestige that society as a whole refuses to grant them. Within a regional martial arts association someone may be an important instructor who is admired, yet to society the same individual is simply a retired factory worker who spends his mornings with other senior citizens in the local park engaged in a feudal practice.

When exported to the west the martial arts can have even more complex interactions with questions of identity. Once again, it is often marginal individuals who are drawn to the martial arts. In the 1970s working class African Americans were drawn to the image of Bruce Lee and Kung Fu because it seemed to offer a new way of defining the self through bodily transformation. Race was not ignored in this process. Rather, the popularity of Chinese martial art provided a space where all types of individuals could start to reimagine how they fit into the American landscape.

For all of the promise of personal transformation, I detect a deep pessimism running through this school of thought. None of the informants in Amos’ field work ever really escape their economically and socially marginal circumstances. In fact, it seems that being a martial arts student or master simply compounds the problem. This is an endeavor that many people in China actually look down upon. The status that is achieved exists only within an imaginary group with little real social clout.

Likewise Bowman and others have noted that there was an unfortunate aspect to the “Bruce Lee Phenomenon” of the 1970s. Lee certainly succeeded in becoming a role model for all sorts of individuals. But very quickly the message of radical, even violent, empowerment seen in his films was transformed into an inner psychological process of self-realization. Energy that could have been diverted into actual political and economic struggle for equality was instead squandered on “personal attainment.” Likewise the Chinese martial arts were quickly commoditized and integrated into western consumer culture, rather than standing as a challenge against it.

As the opening quote makes clear, there will always be a market for philosophical discussion and deep personal transformation. Most people do not come to their first martial arts class because they are happy with everything in their lives and wish simply to defend the status quo with their bare hands. Instead students walk through the door because they are unhappy. There is either something that they are looking for, or something that they wish to change about themselves. The martial arts instructor midwifes this process of personal transformation.

Modern capitalist society and globalization are taking a toll on people around the globe. The global economy provides employment and income, yet it leaves increasing numbers of people feeling marginal and alienated. As traditional social markers and institutions are abandoned there is a need to forge a new identity, to rediscover the deep core of ontological meaning that can serve as a universal reference point, giving meaning to everything else in life.

Young people today are the most likely to find themselves struggling to establish meaning and identity in their lives. Increasingly the traditional institutions of class, religion, race and employment are failing to do this. The promise of meaning, authenticity and transformation become deeply appealing in this situation.

Sunday morning Taiji practice at the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.

The Sociological Approach

The third approach to understanding the popularity and function of martial arts communities seems to be related to the field of sociology. It starts by noting that contrary to the expectations of the previous school, no one really experiences the martial arts in isolation. These are an inherently social activity. One cannot be a “Sifu” without students, and one cannot box, push hands, or even “correct the form,” without a partner.

It then follows that the martial arts rise and fall not so much based on how they empower or create meaning for an individual, but in how they empower an entire group. Groups that are more successful are more likely to attract dedicated individuals. Groups that fail to provide value will lose students and eventually fold. At heart then is the assumption that individuals make choices about which groups to join, yet the social organization itself remains the proper subject of study.

Lin Boyuan, a Chinese historian, has written extensively in this mode. One of the themes that he returns to in multiple places in his work is the topic of urbanization. He notes that both in the Song dynasty, and then much later in the Qing, the martial arts were a critical skill for peasants streaming into the quickly growing cities. Personal protection was an issue, yet it was not the reason why most workers continued to study the martial arts. These individuals even went to considerable lengths to hire instructors and establish schools in their factories.

The martial arts schools they created were critical social institutions because they provided a range of important externalities besides simple combat instruction. The social structure of the school gave students a chance to socialize and network, to find out about new employment opportunities, to secure resources and to create a basic safety net.

This was possible only because these schools created “social capital” or decentralized bonds of trust and reciprocity. Such overlapping networks of trust based on reputation and repeated face-to-face interaction gave a real advantage to workers who enjoyed their support compared to those who did not.

The advantages of membership in a martial arts society did not end with social capital. They were also a means of building “human capital.” A variety of tasks must be performed to keep any organization running smoothly. Instructors need to be hired, dues must be collected. Arrangements must be made for the group’s charitable foundation or Lion Dance team. Finding practice spaces was a never ending task. Some groups and schools even published their own newsletters.

Many of these problems were solved by committees of members working cooperatively together. For poor youth from the countryside, this might be the first time that they were ever asked to sit on a committee, or had to learn how to keep a ledger or to negotiate with a local restaurant. Not only were these skills important for running a successful martial arts association, they are necessary for just about any sort of social advancement in life. Once these skills have been acquired here they can be applied to all sorts of other situations. Martial arts schools were able to act as an incubator for critical human capital reserves.

It is clear that many people have learned all sorts of important skills by becoming involved in the martial arts other than just fighting. Note also that these arguments feel different from the more pessimistic misgivings of the last school regarding the “trap of marginality.” Here the benefits of the martial arts are not simply mystical or emotional, they are actually concrete and empowering. The martial arts society becomes a first step in the process of interacting with the broader community for previously marginal individuals.

This theory also has the advantage of suggesting some of the reasons why we might have seen a decline of interest in the martial arts in the last few decades. The political scientist Robert Putnam (author of Bowling Alone) has noted a decline in all sorts of voluntary activities as Western society continues to evolve. This in turn affects the general level of social capital, making the formation of new groups even less likely.

Alternatively, new technologies have been developed that replace many of the networking and clerical opportunities that martial arts associations used to offer students in the past. There are just easier ways to find out about new jobs and to network with your friends from back home in the age of the iPhone. And in the age of electronic banking, no one really needs a dedicated bookkeeper anymore.

Still, I suspect that this decline is a self-limiting process. The desire for transformation and self-discovery cannot really be satisfied working in isolation. The need to belong is quite strong. People yearn for rituals of community and to experience rites of passage in their own lives. The urge to transcend the self is every bit as strong as the urge towards transformation. In fact, the two are often very closely linked. It is precisely in those moments in which you lose your identity that it is possible to enact a new one.

Conclusion

The previous post has attempted to determine whether the internal martial arts will really be the “next big thing.” At this point the empirical data is far from clear. Yet we do know that the market for martial instruction is always changing. In fact, evolution and realignment seem to be the natural order of things.

We attempted to address this question theoretically by looking at three separate answers, or schools of thought, addressing the question of why the martial arts become popular when the do. Of these I find the sociological approach to be the most satisfying as it provides the most tools for dealing with the traditional martial arts as social groups. While all of the approaches have some strengths and weaknesses, I find it interesting that each is capable of making some strong predictions as to why the internal arts might find a new audience and who it most likely to be. Will it be aging baby-boomers? A new generation of youth seeking for self-actualization? Or possibly economically displaced individuals looking for empowerment through social experience and rituals of belonging?

This will be an interesting question to watch over the next couple of years. Should the internal arts actually go into revival it might shed light on some of the most basic questions in the field of Chinese martial studies.

Morning Taiji group in Bryant Park, New York City.